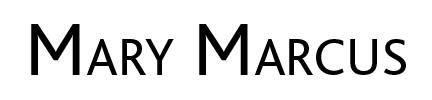

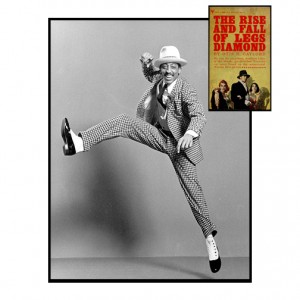

He was tall, he was dark and he was handsome. In my mind’s eye, he resembles the dancer/actor Gregory Hines. And he was the first man I ever loved. I used to sit on his lap and somehow doing that taught me how to read. Though I was very interested in learning to read, chiefly so I could read the Grimm’s fairy tale: “The Fisherman and His Wife,” which is still my favorite fairy tale. I learned how to read by following Jimmy’s long thin finger as he read pulp fiction. The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond, was the book I remember best. And I think the first book I read. It was easier than Grimm. The book had a lurid cover with two women and one very well dressed man, the eponymous Legs dressed in black with black and white spats. To this day, pulp fiction delights me as it delights my husband, my son, and I’m sure my dog, if when sitting on my lap as he often does, could learn to read that way.

He was tall, he was dark and he was handsome. In my mind’s eye, he resembles the dancer/actor Gregory Hines. And he was the first man I ever loved. I used to sit on his lap and somehow doing that taught me how to read. Though I was very interested in learning to read, chiefly so I could read the Grimm’s fairy tale: “The Fisherman and His Wife,” which is still my favorite fairy tale. I learned how to read by following Jimmy’s long thin finger as he read pulp fiction. The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond, was the book I remember best. And I think the first book I read. It was easier than Grimm. The book had a lurid cover with two women and one very well dressed man, the eponymous Legs dressed in black with black and white spats. To this day, pulp fiction delights me as it delights my husband, my son, and I’m sure my dog, if when sitting on my lap as he often does, could learn to read that way.

Jimmy was my father’s driver. It sounds very high falutin for my father to have had a driver. But we weren’t high falutin, much to my mother’s chagrin.

My father was studying to be a lawyer before the War. He came home and ended up like all but one of his other four brothers, selling dresses on the road. He and Jimmy drove all through Texas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma selling dresses. This was in Dallas, Texas where we lived until I was five. And the Uncles started buying up stores and parts of stores in the towns they visited as traveling salesmen.

I didn’t miss my father when he was on the road, and I’m sure the feeling was mutual. But I missed Jimmy with all my heart. I missed him, I’m guessing, the way a little girl is meant to miss her father. To this day, I still can’t figure out what the old man had against me, but it was something huge, out of control and as I look upon it with adult eyes cruel, perverse and wrong.

I thought for years, maybe I wasn’t his child. And that thought comforted me. He and my mother never got along. I heard from one of my aunts they were separated at the time she found out she was pregnant with me and even that she tried to abort me. But my son has his eyes. I wish I could say otherwise, because the only thing that sometimes pains me about my son is that he has my father’s eyes. I was his child. Perhaps he didn’t know it. Perhaps he used it as an excuse for the war he waged against me on every conceivable front.

But I am, for better or worse, his child. And he would know that if he saw my son.

Jimmy always came to work dressed really nicely. He wore little check jackets and vests, and herringbone pants. I believe he instilled in me a sense of style. Certainly no one else in my family was as snappy as Jimmy. He had a pencil thin mustache, and close-cropped hair. His skin was café au lait, and just as little girls say to their fathers, I want to grow up and marry a man just like you, I would always say to Jimmy, “I want to grow up and marry a suntanned man just like you.” I knew about suntan, I did not know about race. That Jimmy belonged to another race that separated him from me and that the divide in those days was as wide as the Grand Canyon was not revealed to me. Was that to my parents’ credit? Probably not, as swartza was every other word out of their mouths.

And then we moved to Shreveport.

My father no longer needed a driver; he now was the proprietor of his own store. Jimmy came with us for the move and then Jimmy disappeared.

The last time I saw him, I had been warned. “You can’t kiss Jimmy anymore.” “You can’t sit on his lap.” I never questioned why; I was sufficiently cowed by the time I was six not to question what they did or said to me to their faces (what I did inside the confines of my brain was quite another thing).

He was working in the basement of the store, doing something with boxes.

Gone were his snappy clothes, gone was the jaunty air of the rogue he always had when he was polishing things on Daddy’s Chrysler New Yorker.

He had on a tan workingman’s uniform. He was sweating. There were deep wet pockets under his arms. And when he saw me he looked embarrassed and sad. But he still smiled. And made a show of it.

I don’t remember what we said. I wasn’t allowed to hug him and he knew enough not to hug me. We stared at each other for a while. Then, he waved and I waved. I hated him being down in that basement, and he hated me seeing him that way.

And I never saw Jimmy again.