When I was eleven, we lived in a great big un-paid for house with a mansard roof, and several empty rooms because there was no money for furniture. Our house was in the new part of Shreveport that was to us, countrified, coming as we did from a track house with an ornamental screen door and two young pine trees in front. Our new backyard was full of old trees and new trees and was nearly an acre. At night in the winter, we could hear foxes.

At the end of the block was a branch of Bayou Pierre, and it was there, one morning in the summer, I went looking for dewberries so we could have cobbler that evening. Aline had been with us by then for more than a year, and though my mother cried all the time, she wasn’t my father, and we laughed at the dinner table. We were broke, of course, and told not to answer the front door in case it was the bill collector, but I was no longer afraid. My father was dead. My mother was at his store trying to make a living. It was my sister, my brother and I under the gentle reign of Aline, who could handle us. Two previous housekeepers, Henrietta notably, had run away screaming waving her hands in the air.

Land around the bayou was dense and the dewberry vines had prickles on them. I had discovered a big clump of them; enough to fill a huge tin can full, and was sedulously picking and eating and biting out prickles from my fingers, when I heard a noise in the bushes.

I was afraid of snakes. I was afraid of foxes. I was afraid of my father coming back from the dead to get me—I was terrified of that. But I wasn’t afraid of black men. And that’s what the noise in the bushes was. A black man. Maybe he was drunk. Maybe he was pissed off. Maybe he was just nuts. (Who could blame him?)

I was almost shoulder high in the marsh and berries, but he was waist high. And his pants were unbuttoned. And his arms were out and he was coming to get me. I dropped the can and ran out of that rich patch of berries I’d found on Bayou Pierre, up the tar road and into the kitchen. I was plenty scared by the time I reached Aline’s warm arms. I was probably shaking like a leaf.

Aline wanted to know what happened.

I told her a man had chased me.

“Yes,” she said. “What happened? Did he get you?”

“No,” I told her. “I ran.”

“That’s good,” she said. And she looked me up and down. And she sighed. I could tell she was relieved.

She looked me in the face. “You sure about that?”

“Yes,” I said.

Once again she looked me up and down. “What’d he look like? Was he black?”

Something in her look and in her voice told me what to say.

“White,” I told her. “He was white.”

“You sure about that?”

“Yes.”

“So, do you want to call your mama?”

“No,” I said.

We made some jello for dessert that night, and I stayed away from the dewberry patches for a while. And to this day, no crazy black man has ever menaced or scared me again.

I thought of that long ago summer this morning, when I read the Op Ed pages of the New York Times. “Louisiana’s Color-Coded Death Penalty.”

“In Louisiana of today, a black man is 30 times as likely to be sentenced to death for killing a white woman as for killing a black man. Regardless of the offender’s race, death sentences are six times as likely—and executions 14 times as likely—when the victim is white rather than black.”

Louisiana has the worst record in the country. It’s right up there with repressive regimes in the second and third worlds.

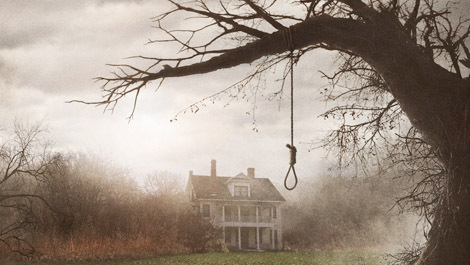

Back then, I knew, if not the statistics, certainly what would have happened if I told Aline that a black man had chased me with his pants down. And she had called my mother. It would have meant, five, six maybe a whole dozen black men would be captured and probably lynched.

How can it be possible that all these years later, on some level this system is still operating in the land of the free and the brave?

In Louisiana 2016. In Ferguson 2015. The list goes on and on and on.

What are we to do about it?